Mother Jones: The Science Behind Ethiopia’s Hunger Crisis

The country's last mega-droughts killed hundreds of thousands. Could the same thing happen again?

Ethiopians in the rural Ziway Dugda district await distribution of emergency food aid in January. Mulugeta Ayene/A

This story first appeared on Mother Jones.

Tens of millions of people are facing a hunger crisis as a widespread drought is decimating crops and livestock in Ethiopia and southern Africa. The drought—which has received far less US media coverage California's dry spell—could prove to be one of the most devastating consequences of the ongoing El Niño event that is wreaking havoc on global weather.

What's happening?

Last month, the United Nations found that drought in southern Africa has exposed 14 million people to hunger. In South Africa, 2015 was the driest year on record since 1904. And across huge swaths of Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, and elsewhere, conditions are the driest they've been in the last 35 years, according to the UN:

Famine Early Warming System

The majority of staple grains in these countries are produced by small-scale farmers who don't have access to irrigation, making them especially vulnerable to low rainfall. And because most crops there are grown for subsistence, rather than for sale, a bad harvest has graver consequences than simply lost income. From the Associated Press:

Families are going up to two weeks without a solid meal in Madan'ombe, a village in Masvingo province in southern Zimbabwe…Loveness Ndlovu and her six children prepare smoked fish on a fireplace in a round hut devoid of any other food. The children, who last tasted meat a month ago, know better than to salivate over the six catfish caught in a lake by their father, Zimaniwa.

"They can only touch the fish, they cannot eat," Ndlovu said. "It's two weeks now since I last had a proper meal. If it gets worse, I will have to beg from other villagers so I can at least feed my kids."

The parents plan to barter the fish for other foodstuffs such as maize. Ordinarily, the entire family would be busy in the fields, weeding a knee-high maize crop. Now they can only watch as skinny donkeys graze on failed crops. Vast fields lie dry and fallow.

The last resort is foreign food aid; last month, Zimbabwe declared a state of emergency in the hope of mobilizing a greater response from the UN's World Food Program and other donor organizations.

The most severe drought impacts could be further north in Ethiopia, the site of massive famines in 1973 and 1984 that left hundreds of thousands of people dead. According to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, a US-government-led coalition that tracks hunger crises, 10.2 million Ethiopians are now in need of emergency food aid. Only about a quarter of the aid that's now required has come in so far, and current aid supplies are expected to run out by April.

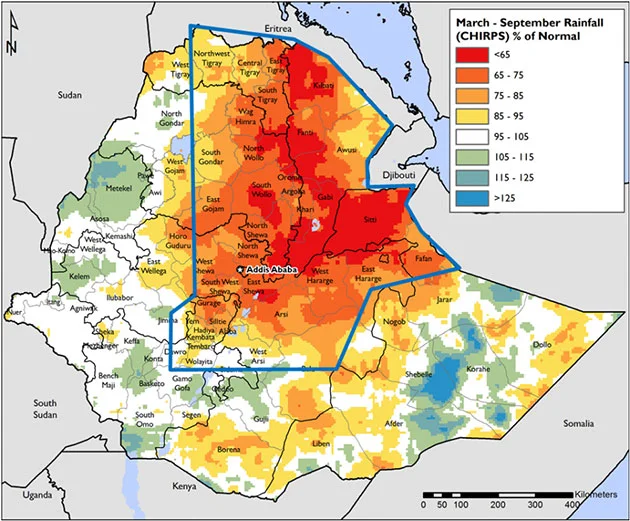

Here's a look at rain conditions in Ethiopia during the summer and fall of 2015, a period which is normally expected to provide rain for winter crops. As you can see, huge parts of the country received less than three-quarters of their typical rainfall:

FEWS

A spokesperson for Doctors Without Borders said the situation in Ethiopia has not yet developed into a full-blown famine but added that "if the next rains also fail and food distributions are not properly organized, far more people could become malnourished."

Fortunately, whatever happens with the rains, the country's political situation is much more stable than in previous decades, when neglect and human rights abuses by the government were as much to blame for the famines' death tolls as were the climatic conditions. From the Washington Post:

These days, early warning systems alert the government when famine threatens, and in 2015, these kicked into action after the spring and summer rains failed, leaving herders trapped in desert pastures and farmers with extensive crop failures across the north and east of the country.

"I remember 1984, people would migrate or just die," said Mohammed Abdullah, a haggard farmer in his 40s in a village in the highlands of East Hararghe, about 300 miles east of the capital. Normally, villagers would be harvesting corn and sorghum now, but the terraced hillsides were largely empty. "This time, the government response is on time and coming before people leave."

He shuddered, though, when asked what would happen if the handouts stopped, as may happen if an additional $700 million in funding is not secured. "If there was no support and the rains don't come, people will start dying."

Is El Niño to blame for Ethiopia's drought?

Most likely, yes. During El Niño years, warm ocean temperatures in the Pacific slow down natural circulation in the atmosphere, producing a ripple effect on rainfall across the globe. South America tends to get above-average rainfall during El Niños—hence the link to a population boom in Zika-carrying mosquitoes—while Southeast Asia gets below-average rain. Coastal East Africa—Kenya and Somalia—is expected to get above-average rain. But next door in Ethiopia, the elevation is much higher, and that extra moisture doesn't make it in.

"So Somalia becomes wetter, but in Ethiopia it actually becomes drier," explained Jessica Tierney, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Arizona.

That effect is particularly pronounced in the summer, which was exceptionally dry in 2015 (see the map above).

"This was forecast ahead of time and the world should not be surprised."

"The major reason for the drought in that region is the shortfall of precipitation during the summer monsoon season, which is the primary precipitation season in that region," said Park Williams, a climatologist at Columbia University. "This is consistent with the general effect of El Niño."

In other words, we should have seen this drought coming, said Richard Seager, another researcher at Columbia: "This was forecast ahead of time and the world should not be surprised."

Some relief could be on the way soon. Williams said that the upcoming spring rainy season, which is particularly important for agriculture, is generally less sensitive to El Niño, so "hopefully the seasonal forecast models are correct and Ethiopia starts getting some good rain beginning in March or so."

But as in much of Africa, good weather data is scarce, so any predictions will be much shakier than for, say, California. In any case, lasting drought relief will have to wait for the major monsoons this summer—will they be missing for another year, or will they return?

"The area hurting most from this drought will need to wait until June or so to see whether their luck can turn around," Williams said. Unfortunately, he added, "the El Niño event will very likely not be entirely over [by then]."

What about climate change?

As with other individual weather events, scientists are loath to blame global warming per se—especially since El Niños are a fairly common, cyclical occurrence.

"There is no good reason to assume the current drought is climate change-related," Seager said.

As for what the future holds, that's a thornier problem. There's some evidence that climate change could lead to exceptionally strong El Niños becoming more common, but the science is far from settled on that question.

"There is no good reason to assume the current drought is climate change-related."

There's even less agreement about what strengthening El Niños, and climate change in general, could mean for East Africa. That's because the region's main seasonal rainy periods—one from September to November, another from March to May, and a short but heavy monsoon in the summer—have proved a headache for atmospheric scientists to nail down in models.

Models produced by the UN'S Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change "suggest that all of East Africa should get wetter" in a warming world, Tierney said. But, she added, "what we're actually seeing on the ground is the area getting drier."

At the same time, this year's El Niño effect has been compounded by a long-term decline in precipitation that is not well understood. Rains in Ethiopia have declined by up to 20 percent since the 1970s. But it's not clear if and how that could be driven by global warming.

The upshot is that the current drought is a product of El Niño making a bad situation worse. The question now is whether the Ethiopian government, and its partners at the World Food Program and other aid organizations, will be able to prevent a replay of the humanitarian disasters we've seen too many times before.